Los Angeles, the city of angels, a nickname derived from the cities name when translated from its origins in the Spanish language to English (‘the angels’). Nathanael West tackles the religious imagery of the city in The Day of the Locust by stating that many went ‘to California to die’[1]. The city is described as ‘a paradise on earth’[2], a heaven, but this is not the picture painted by the literature produced from the Californian city in the 20th century.

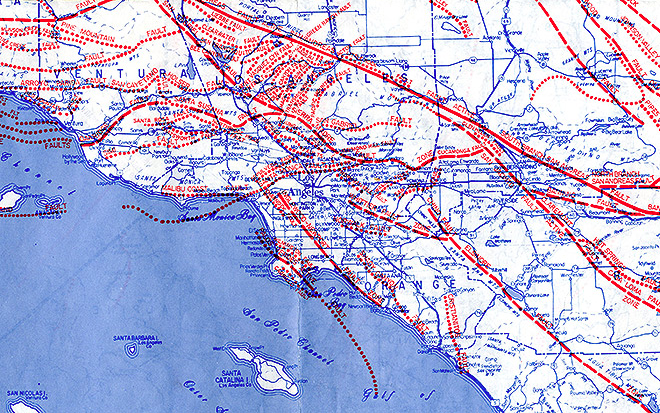

Los Angeles may be a manmade paradise for some, but when considering the ground it is built upon, Los Angeles is one of the most flawed cities in the world. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the fault lines of the area are a disaster waiting to happen, a ticking time bomb waiting to explode. The Burning of Los Angeles as described by Tod in The Day of the Locust, and Arturo Bandini’s earthquake vision in Ask The Dust, are extreme portrayals of potential realities, the latter being based on the Long Beach 1933 earthquake (as explored in the next section).

Fig. 1 <https://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/citydig-scare-yourself-silly-with-this-map-of-las-fault-lines/> [accessed 1st December 2021]

Even Didion’s ending in Play it as it Lays draws the same ideas of fire and disaster, with ‘the room […] blazing with light’[3]. The pessimistic dread of the city is envisioned by prolific writers that all moved to California. As Fine mentions, ‘virtually all of [these writers] until the most recent few decades – were themselves outsiders, newcomers, visitors. This must be the starting point for any discussion of Los Angeles fiction.’[4] Didion and West both moved from New York, while Fante moved from Colorado. Fine points out that ‘the instability of the land at, or near, the ocean’s edge […] equated with the instability of the migrant population itself’.[5] These two key factors have resulted in Los Angeles’s fictional identity being focused on instability and a confused perception of the city.

Fante has a great example of this: ‘You pretty town I loved you so much, you sad flower in the sand, you pretty town’[6] are the words of Bandini in Ask The Dust, just a mere few pages in. The juxtaposition of ‘pretty town’ and ‘sad flower’ is unquestionable, the past tense in the phrase ‘I loved you’ painting a vivid image of the city in such few words. Los Angeles has a flawed beauty. It is so pretty at first sight, yet so sad when the ‘false faces that [it] has been known to wear'[7] are seen through, a ‘sun-dried dystopia’[8] built on faulty ground being the reality.

[1] Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust (Penguin: Milton Keynes, 2018), p.27

[2] ibid, p.102

[3] Joan Didion, Play it as it Lays (4th Estate: London, 2017), p.213

[4] David Fine, ‘Starting Points’ in Imagining Los Angeles: A City in Fiction (University of Nevada Press: Nevada, 2004), 1-25 (p.15) <https://moodle.brookes.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/2955138/mod_folder/content/0/David_Fine_Chapter_1_Starting_Points_in_Imagining_Los_Angeles.pdf> [accessed 4th December 2021]

[5] David Fine, ‘Down and Out in Los Angeles’ in Imagining Los Angeles: A City in Fiction (University of Nevada Press: Nevada, 2004), 179-206 (p.181) <https://moodle.brookes.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/2955138/mod_folder/content/0/David_Fine_Down_and_Out_in_Los_Angeles_from_Imagining_Los_Angeles.pdf> [accessed 4th December 2021]

[6] John Fante, Ask the Dust (Canongate: Edinburgh, 2018), p.4

[7] Stephen Cooper, ‘Fante’s Eternal City’ in Los Angeles in Fiction (University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, 1995), 83-99 (p.83) <https://moodle.brookes.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/2955138/mod_folder/content/0/Stephen_Cooper_John_Fantes_Eternal_City.pdf> [accessed 4th December 2021]

[8] Mark Laurila, ‘The Los Angeles Booster Myth, the Anti-Myth, and John Fante’s Ask the Dust’ in John Fante: A Critical Gathering (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press: New Jersey, 1999), 112-121 (p.112) <https://moodle.brookes.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/2955138/mod_folder/content/0/Mark_Laurila_Los_Angeles_Booster_Myth_the_Anti-Myth_and_Ask_the_Dust.pdf> [accessed 4th December 2021]